“Preparing for War – Logistics: When war was imminent, Parakrama Bahu made special arrangements for supplies to be made available, whether of food, armaments, medical requirements and money, for the army or the civilian population at large… So far as the civilian population was concerned, Parakrama Bahu made sure that the cultivable areas would be adequate, by enlargement if necessary, to provide the grain needed by the troops and by the civilians. (Culawamsa Ch.76). Parakrama Bahu superimposed on the foregoing arrangements two Chief Ministers; a Minister of War and the other, a Minister of Civil Administration, who were responsible to him for the coordination of the logistic effort for the Army and civilians.”

By Major General Anton Muttukumaru, The Military History of Ceylon – An Outline (Navarang, 1954)

The foregoing passage in Major Gen. Anton Muttukumaru’s book about Sri Lanka’s military history suggests that the military apparatus of the ancient Sri Lankans was sophisticated, and that they were keenly aware of the importance of supplies and logistics in warfare.

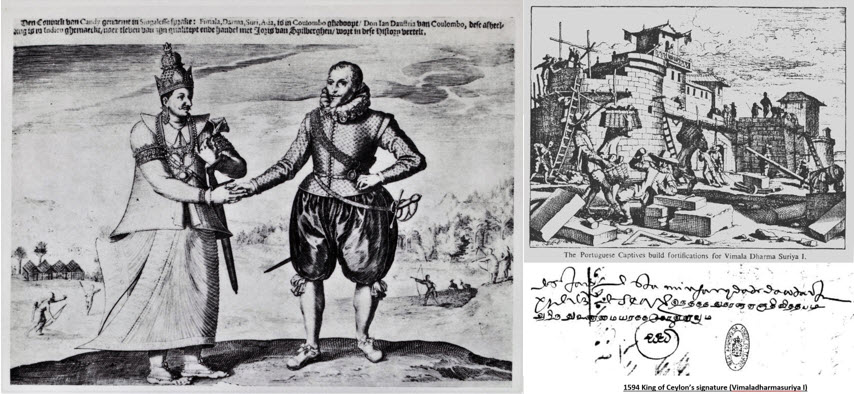

King Vimaladharmasuriya 1 successfully used a strategy of classic guerrilla warfare combined with a strategy of depriving the enemy of supplies to achieve a decisive victory. In 1594, a 20,000-strong Portugese army commanded by the Portuguese Captain-General Pedro Lopes de Sousa headed to Kandy for the purpose of installing Queen Dona Catharina on the throne. Rather than fighting such a large force directly, King Vimaladharmasuriya 1 tactically withdrew from Kandy to the surrounding jungles which allowed the Portuguese to falsely believe that they had won a great victory. After three months of occupying Kandy, the Portuguese army running short of food and supplies and facing regular guerrilla attacks and mass desertions was forced to retreat back to Colombo. During the retreat, the Portuguese army was annihilated at the “Battle of Danture” with the loss of many famous Portuguese military leaders of the day.

During the European imperial period, the kingdoms of Sitawaka and then Kandy fought major European powers to a standstill until the final capture of the island in 1815 by the British. Numerous European armies, marching in fixed formation, wearing brightly coloured woolen tunics, were decimated by ancient Sri Lankans. Though the Kandyan kingdom did not have a large standing army, the king could mobilize a large force of irregulars at short notice using the feudal system then in existence. With knowledge of the terrain and living locally, they did not require a complex supply chain to sustain themselves.

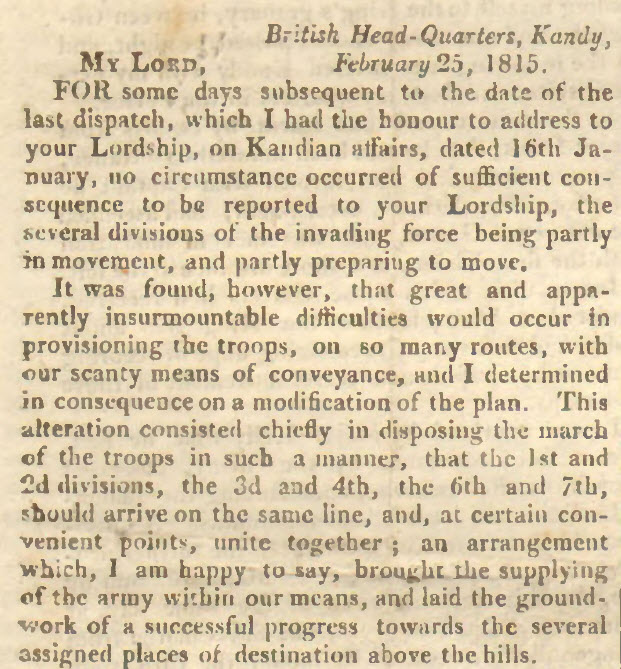

On the other hand, European armies operated on a supply chain that was susceptible to disruption due to the guerrilla tactics employed by the ancient Sri Lankans. Even after the capture of the island, uprisings such as the Uva rebellion, show the skill and bravery of the ancient Sri Lankans in fighting the most powerful imperial power of the day.

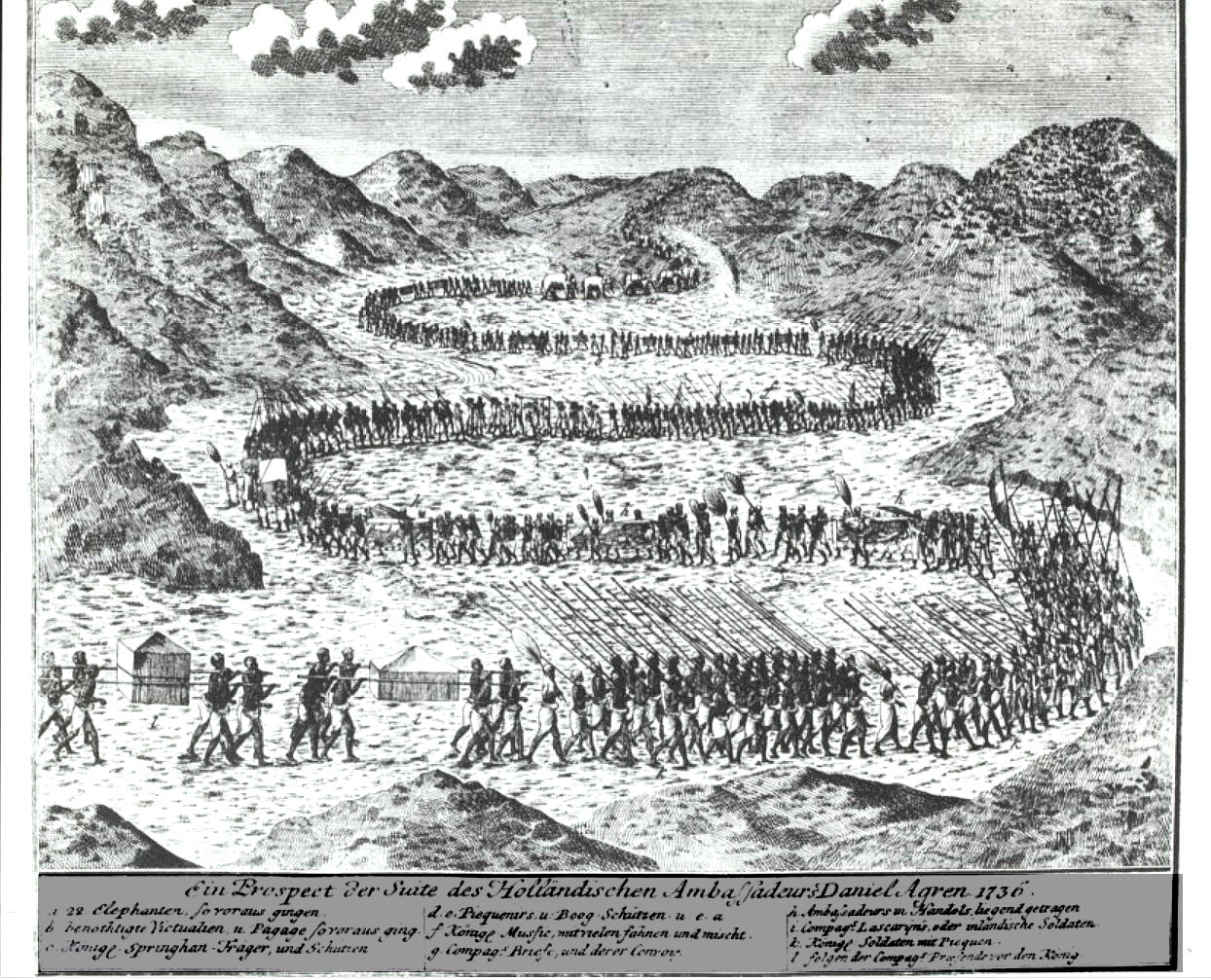

Illustrations are from Phillip Baldaeus’s “A True and Exact Description of the Great Island of Ceylon.” There was a big contrast between the European armys trained to fight in European environmental conditions and native armys of Sri Lankan kings who were highly proficient in irregular warfare. The Portuguese, Dutch and even the British used a combination of European mercenary troops and local troops. On the left, Dutch soldiers landing in Jaffna, Sri Lanka. On the right, the Dutch Ambassador being taken to the Court of the Kandyan King in 1736.

The following account of the heroic and brilliant tactics used by ancient Sri Lankans in the Uva Rebellion highlight this point:

John Davy, An account of the interior of Ceylon, and of its inhabitants : with travels in that island (1821)

The insurgents “had recourse to stratagems of every kind and took every possible advantage of the difficult nature of the country and of their minute knowledge of the ground. They would waylay our parties and fire on them from inaccessible heights or from the ambush of an impenetrable jungle; they would line the paths through which we had to march with snares of different kinds, such as spring guns, spikes etc. and in every instance that an opportunity occurred, they would show no mercy and gave no quarter.”

Ancient Sri Lankans had a martial tradition that pre-dated the arrival of Europeans. Martial arts such as Angampora, which is unique to Sri Lanka, are evidence of this tradition. Furthermore, metallurgy and weapon making skills were of a highest standard and continued up to the point till the country was captured by the British. During the European imperial period, Sri Lankan craftman produced some of the finest firearms, swords, and military accessories as shown in the following museum artifacts from the 17th through 19th centuries. Some of the firearms produced in Sri Lanka during that period are described as the finest east of Persia. Many of these skills were lost after the British conquest of Sri Lanka.