Size and composition of the Ceylon Garrrison at Turn of Century

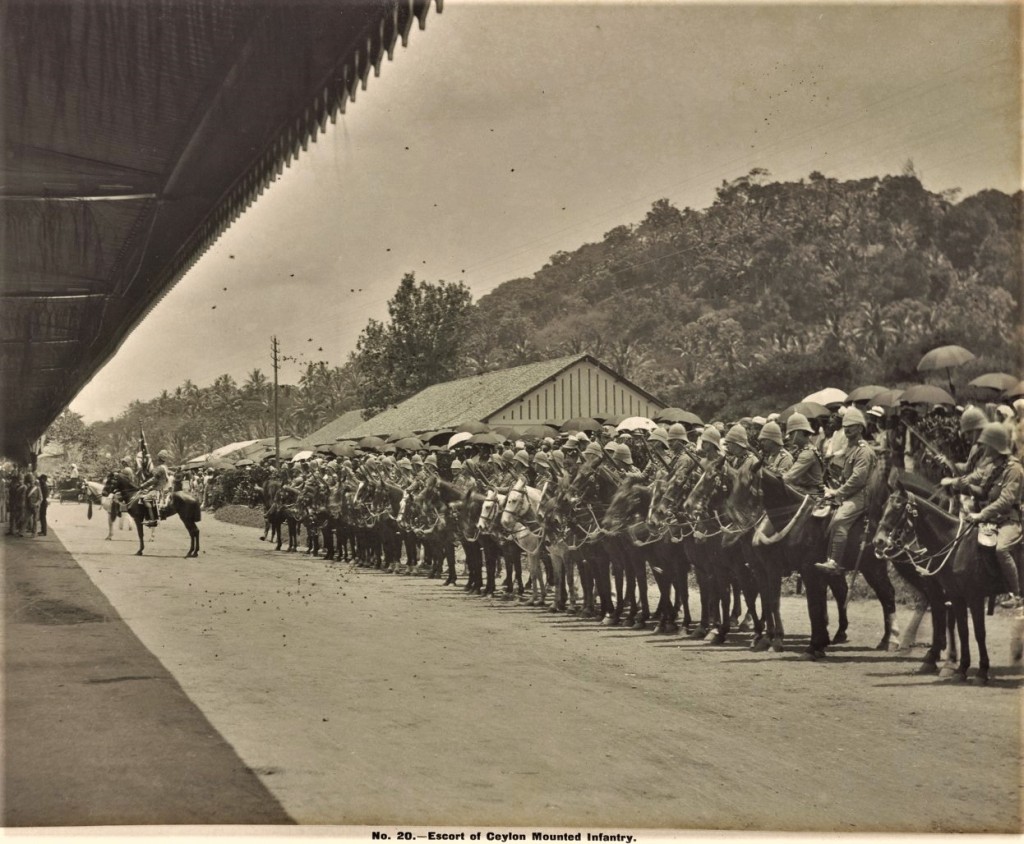

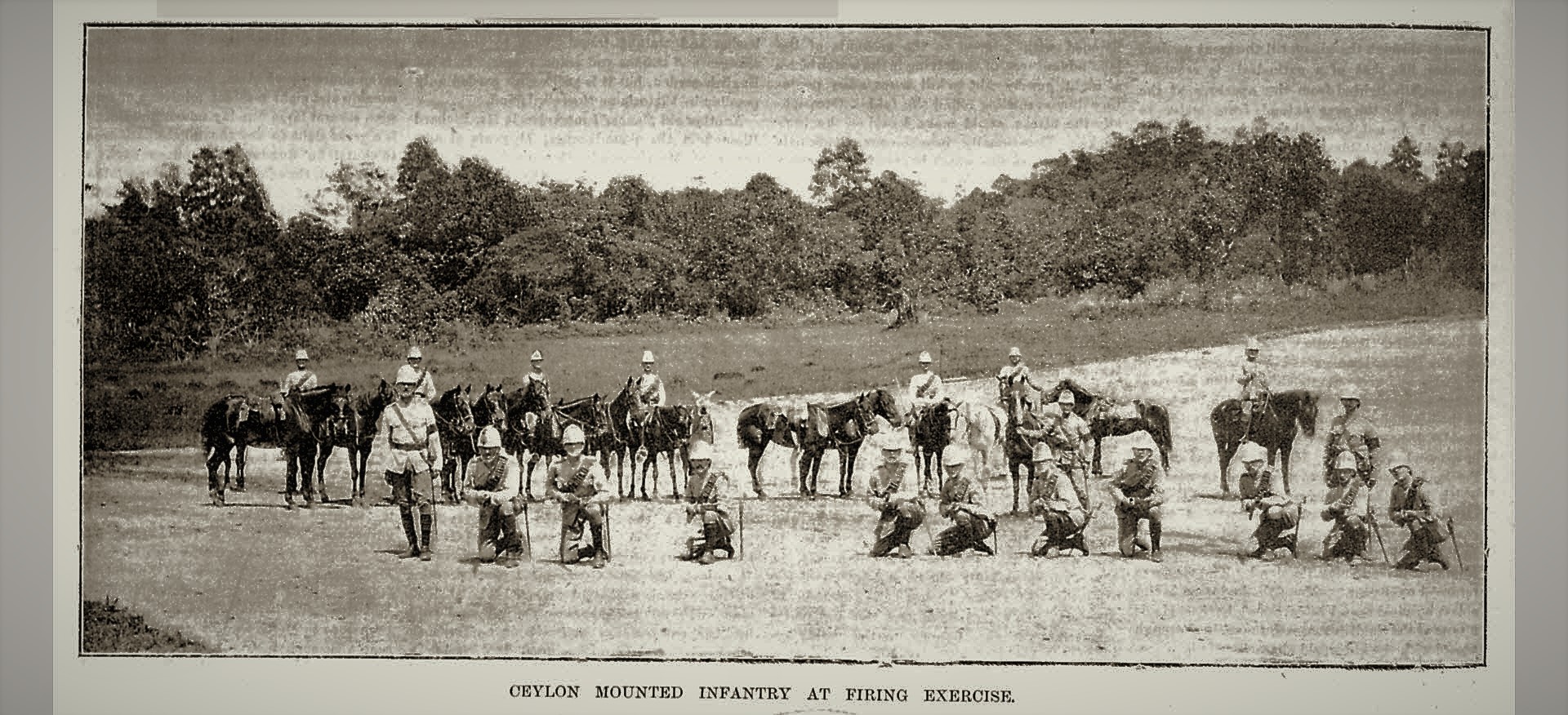

Although there was a Ceylon Regiment composed mostly of Malays, Ceylonese and persons of African origin till the 1870s, the origin of the Sri Lanka Army can be traced to the Ceylon Light Infantry Volunteers formed in 1881. This all volunteer force was set-up by proclamation of the Lt Governor. It was commanded by British officers with Ceylonese in the ranks. The force received an addition in the form of a mounted infantry company in 1892, and in 1900 this contingent was sent to South Africa in the Boer War. In 1910 the volunteer corps was redesignated as the Ceylon Defence Force.

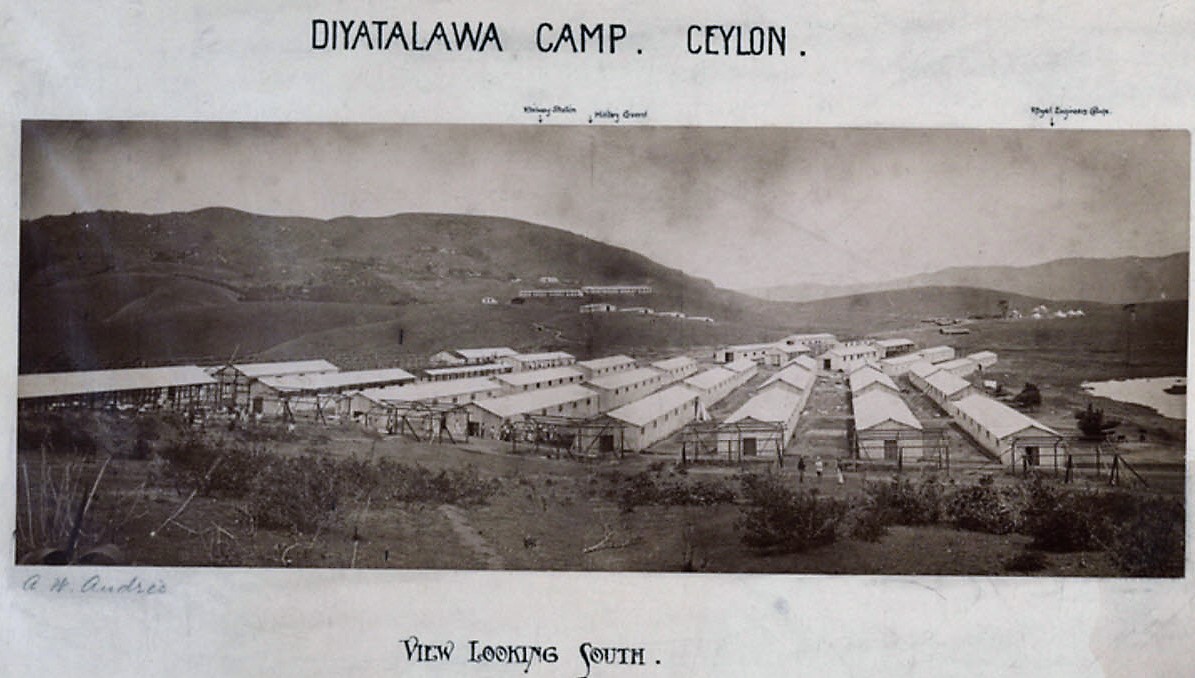

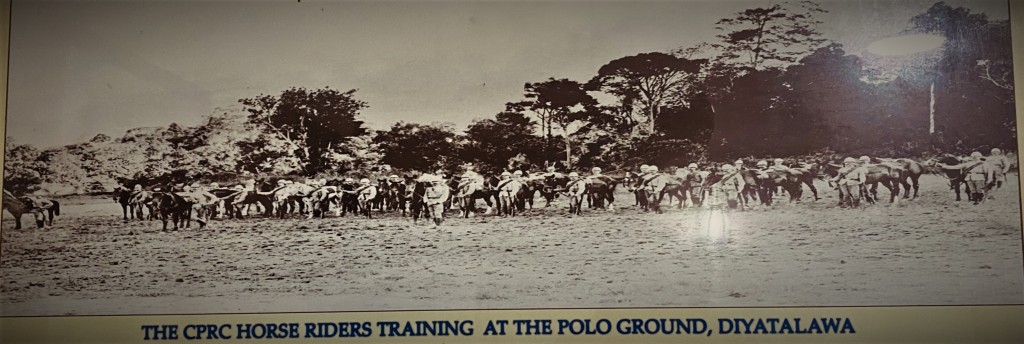

One of the Outcomes of the Boer war was the mass internment of 5000 Boer prisoners in then Ceylon between 1899 and 1902 in Diyatalawa

POW Camps in Ceylon During the Boer War

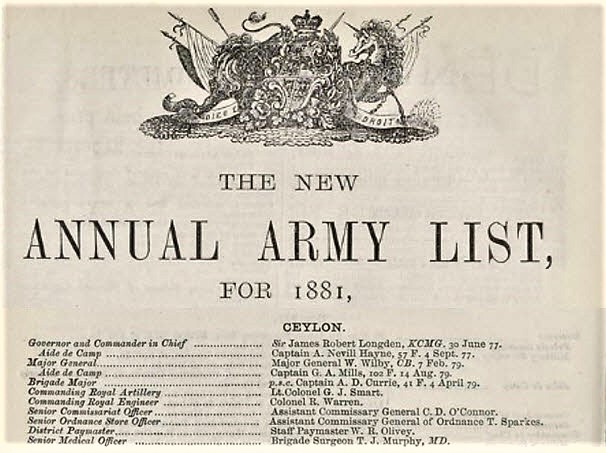

The 1881 Army list shows two senior Commissariat Officers with responsibility for provisioning and Ordnance of the British Ceylon Garrison. From 1897 through 1949, the Army Service Corps took over the commissariat and logistics functions of the British Garrison. Eventually those functions (as they related to the Ceylon Defence Force) were taken over incrementally by the Sri Lanka Army Service Corps’s predecessors (the CS&T and CASC).

Ceylon Mounted Infantry in the Boer War

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1YF_-z1l8-Q5H-3e9xohabDZZt20t34hM

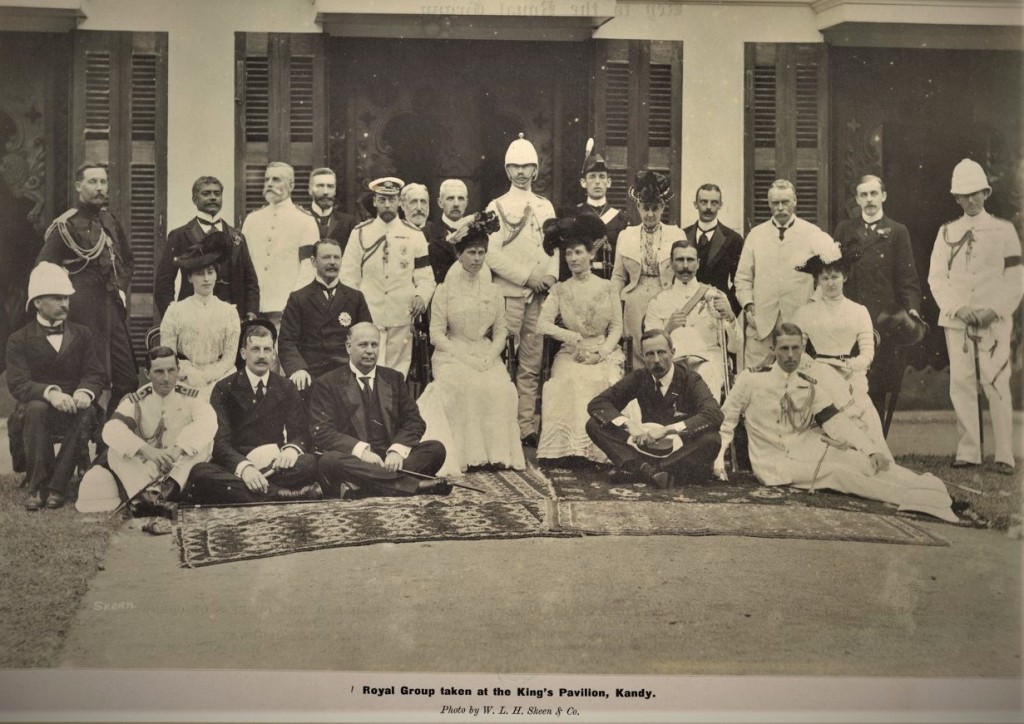

Ceylon Defence Forces at the Turn of the Century

The British garrison from the dawn of the 20th century through the pre-war period leading up to WW2 was a small colonial militia that reflected the minimal security needs of then Ceylon. The colonial administrators of Ceylon perceived the country as an idyllic colonial outpost with minimal threat to colonial rule. Hence, there was little incentive to expand the force until WW2.

The following excerpt is from the 1904 Army Service Corps Journal:

“The Volunteer Force could no doubt be easily and largely increased on an outbreak of war, and it is safe to assume that both Europeans and Burghers would be prepared to make considerable sacrifices if need be in defence of the colony. The native inhabitants to all appearance are also loyal and contented; but in the event of an enemy landing and gaining an initial success—especially if trade were interrupted and rice scarce—the situation would not be without a certain.”

The Ceylon Garrison in 1904 consisted of Regular troops and Volunteers.

Regular troops (1,300 European and 250 native troops)

– 2 Companies Royal Garrison Artillery

– 2 Companies Ceylon- Mauritius Battalion

– Royal Garrison Artillery 1 (Ceylon) company Sub-marine Miners

– Royal Engineers 1/2 (Fortress) company

– 1 Battalion Infantry and detachments Army Service Corps

– Royal Army Medical Corps

– Army Ordnance Corps

– Army Pay Corps

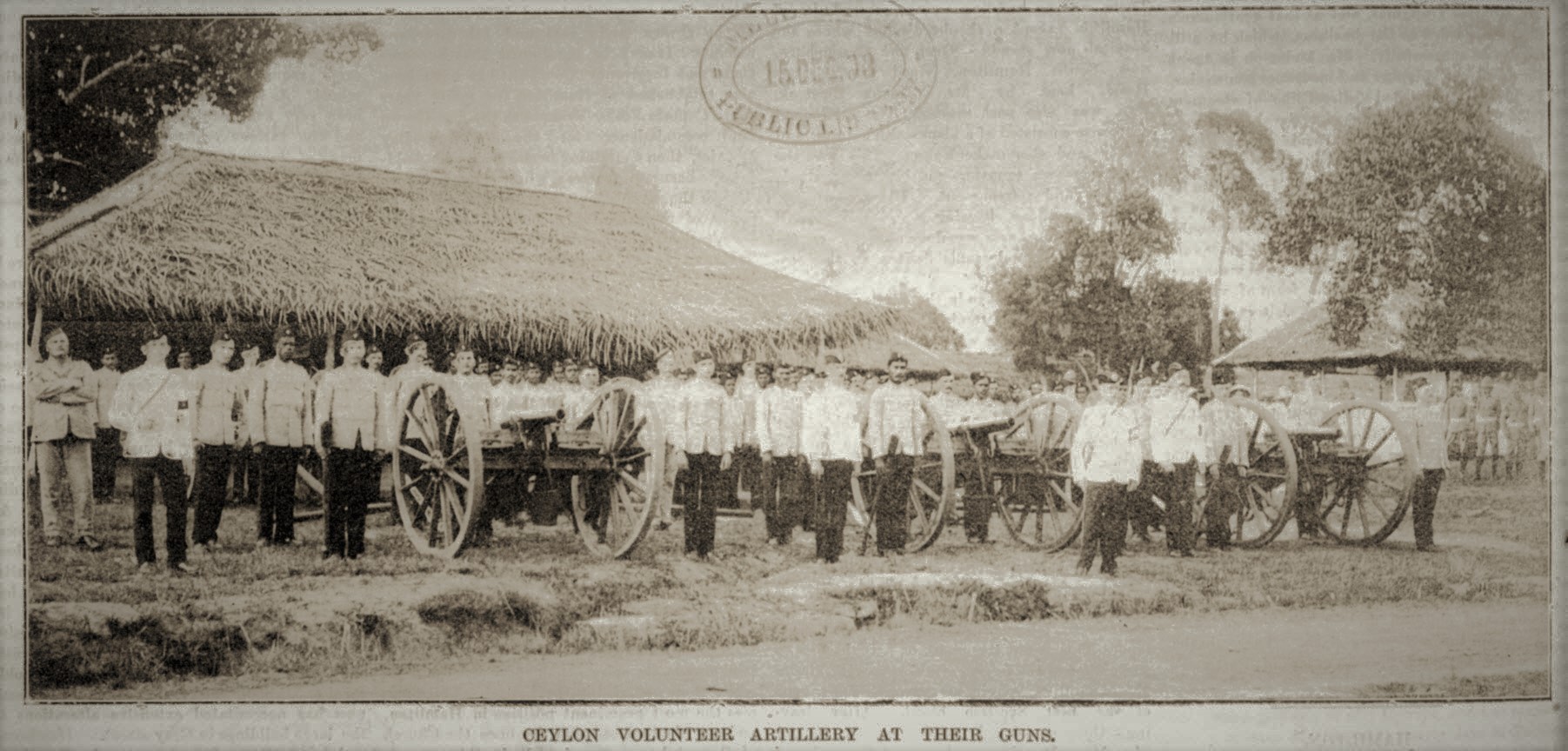

Volunteers (total 2,500)

– Ceylon Artillery, strength about- 160.

– Ceylon Mounted Infantry, strength about 130

– Ceylon Light Infantry, strength about 1,100

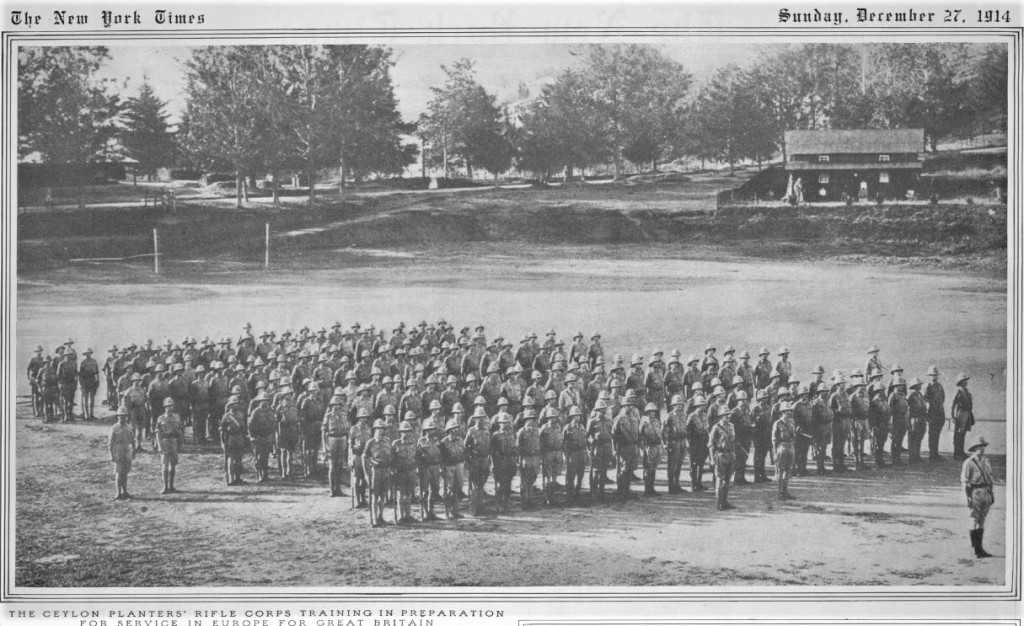

– Ceylon Planters’ Rifle Corps, strength about 700.

– Cadets, strength about 420,

Civil Police 1,730 all ranks (including 36 Europeans)

Many of the volunteers were British planters who had a service background. The tradition of volunteering continued well into the post-colonial period. Unlike in India where the army was constantly battling tribal groups on the fringes of the North-West frontier, there was hardly any opposition to the colonial presence in Ceylon during this period. In his memoirs the British author Leonard Woolf fondly recalls how as a 26 year old Government Agent he administered the vast swath of land that made up the Hambantota district. He accomplished all of this with the aid of a small kachcheri staff and a solitary police sergeant.

Impact of World War 1

The contributions of the British-Indian army in WW1, which fielded 1.5 million combatants by the end of the war and had 74,000 casualties, including 11 Victoria cross recipients, dwarfed those of other colonies.

By contrast, Ceylon sent roughly 2,300 “volunteers” to the UK. They included 100 men and 5 officers of Ceylonese and British origin of the Ceylon Sanitary Corps (CSC), which was attached to the Royal Army Medical Corps. The CSC’s main tasks were to “clean up foreshores and areas designated for army encampment, water testing and pumping, disinfection and pest control.” The CSC operated around Basra, Baghdad and Hinaidi of then Mesapotamia (Iraq).

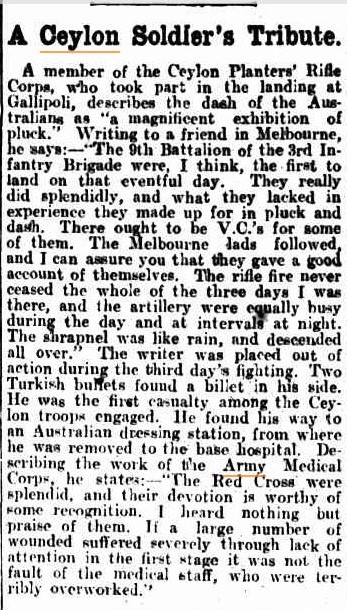

In addition to the CSC, 230 personnel from the Ceylon Planters Rifle Corps (CPRC), which was made up of young British tea or rubber planters, were deployed. A contingent of officers and men of CPRC left Ceylon for Egypt in October 1914 where they served under the 1st Australia New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) defending the Suez Canal till March 1915. The remaining half of the CPRC served with various British units. On April 1915, the CPRC personnel with the 1st ANZAC headquarters landed at Gallipoli. The disastrous Gallipolli campaign lead to the capture, evacuation and imprisonment of a large number of Commonwealth forces.

CPRC in Gallipolli (Click to View Link to NZ Archives)

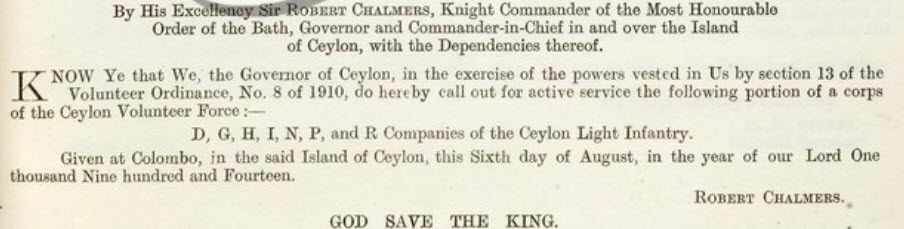

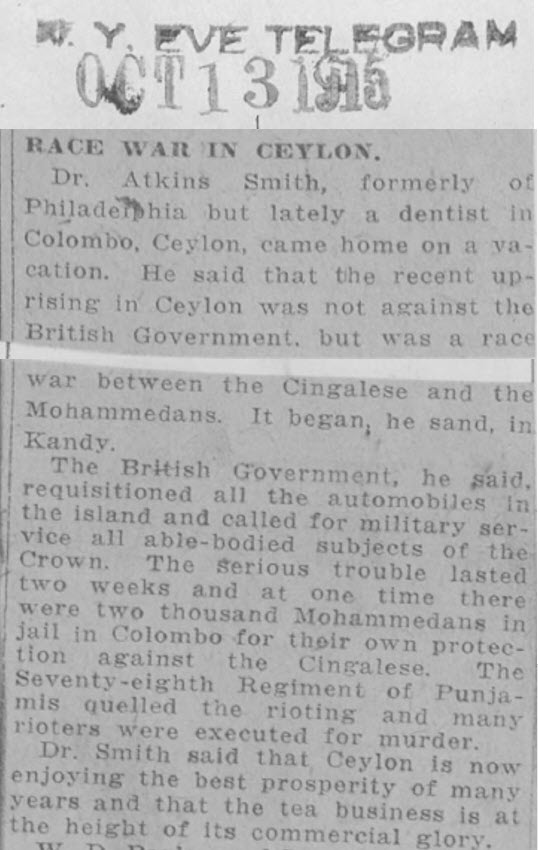

The home front was largely peaceful except for the Sinhala-Muslim riots that took place in May 1915. At the outbreak of war in 1914, the Governor Sir Robert Chalmers mobilized the Ceylon Engineers Volunteers. This was followed by the mobilization of the Ceylon Artillery Volunteers, the Ceylon Light Infantry, the Ceylon Mounted Infantry and the Ceylon Volunteer Medical Corps. The Ceylon volunteers, who were almost all British, were supplemented by the 28th Punjabi Regiment and a regular Artillery and Engineer company. In response to the riots, martial law was imposed on June 2, 1915 and the riots were brutally put down with “suspected looters and arsonists shot without trial by the Volunteer forces and Town Guard.” Chalmers was succeeded by William Manning (10 September 1918 – 1 April 1925), a British administrator with a military background who had fought in various colonial wars in Africa and the Indian sub-continent.

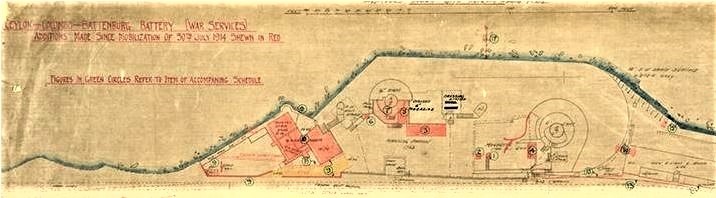

The threat to Ceylon’s territorial waters came from the German cruiser SMS Emden, which was operating in the Bay of Bengal from 5 September 1914. SMS Emden sank or captured 25 Allied ships before being run aground off the Cocos Islands by the Australian light cruiser HMAS Sydney on 9 November 1914. After this episode, the only trouble to the shore and harbour defences came from British and Allied shipping ignoring regulations and not signalling properly when entering the port of Colombo. Warning shots were fired from the harbour defences (see map of the Battenberg Battery, which formed part of the harbour defences).

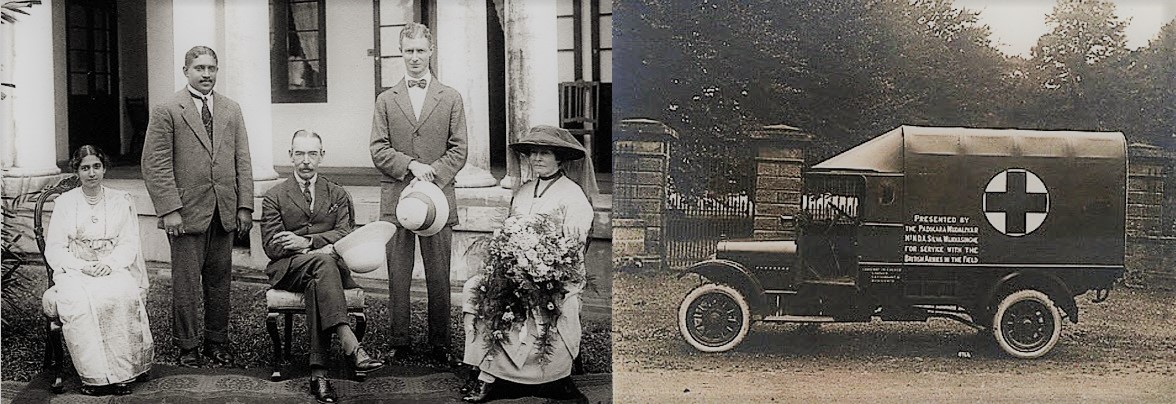

Left : Victory and Peace Celebrations at Richmond House. Group photograph taken with Brigadier General Sir William Henry Manning, K.C.M.G., K.B.E., C.B. Governor of Ceylon, who gave a gracious message to be delivered to the 10,000 people who were assembled on the invitation of Mudaliyar N. D. A. Silva Wijayasinghe Siriwardene to celebrate the Victory and the conclusion of Peace. Right : Motor Ambulance presented by the Mudaliyar to the War Office for service with British Armies in the field

WW1 was a turning point in the field of transportation, supplies and logistics in warfare. Large scale use of supply trains and trucks would replace horses and mules.

For the British empire, the war was a major turning point that would lead to its decline and eventual dissolution at the end of WW2. At the end of this epoch time, the foundational elements of the future Sri Lanka Army were still in the making. Despite the limited presence of Ceylonese officers in the overall Ceylon Defence Force, Ceylonese were well represented in two regiments in particular: the Ceylon Light Infantry and the Ceylon Medical Corps. The trend towards Ceylonisation would continue to accelerate in the decades leading up to WW2.

Additional Resources

Ceylon Garrison 1914

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1H–DLP3J0UFgsgN7AiAJyt18xDbw2m5D

Ceylon Garrison 1918:

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1dTlebNLe7-l8zE1O-tHXIcimk_TsVZXI

Composition of the Ceylon Defence Force in 1918, Part 1

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1j4ZS7EtU2H5Ut2_Nd8lGhfUjJdiBCTtS

Composition of the Ceylon Defence Force in 1918, Part 2

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1XGLBFn3W0h2O5SradRgq1XUQlAv2E3q2

Composition of the Ceylon Defence Force in 1918, Part 3

https://drive.google.com/open?id=17PmCZ-wizbBToaU-6M9LoD2GrRtVNxnw